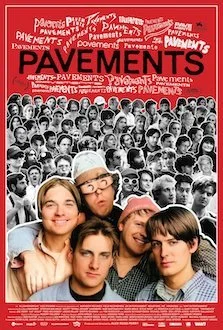

Direction: Alex Ross Perry

Country: USA

The greatness of the American indie rock band Pavement is not matched by this fragmented, experimental docufiction written, co-produced, and directed by Alex Ross Perry. The director of Queen of Earth (2015) and Her Smell (2018) opts for an uninspired artistic approach, where actors portray the musicians, a group of performers rehearse and stage a musical set to Pavement’s songs, and a museum tribute to the band catches everyone—including the band members—off guard.

Briskly edited, the film plays like a disjointed collage that is more tedious than exiting. The actual story of the band is entirely eclipsed by these misguided artistic ambitions. The only aspect that offered a hint of interest was the contrast between the irreverence of youth and the band’s more cerebral, detached presence today. There’s an overuse of split screens, overlapping sounds, chaotic movements…

Sadly, Pavements fails to do justice to Stephen Malkmus and his unforgettable band.